Overview

Occasionally one hears someone say that “philosophy” is an essentially European term that should not be applied to the thinking of Asians. Jitendra Nath Mohanty, (1992, pp. 283-290) recounts the misgivings of Edmund Husserl, Richard Rorty and Martin Heidegger on this matter. I think that such a sentiment probably rests on a misunderstanding of both what philosophy has traditionally been in Europe, and in places that inherited European cultural traditions, and what some people like to call religion has been in Asia. The frequently encountered misconception about Western philosophy is that it is entirely intellectual in nature and has no practical dimension for improving the character of the person who engages in it. The misconception about Asian religions is that they are entirely transcendental in nature and therefore have no more than a passing need for “mere” rationality. A study of the history of Western thought, however, shows that it has traditionally been—and in many quarters still is—very much about improving character and achieving something very like liberation; a study of Asian religions, including Buddhism, shows that most of them rely heavily on a rational dimension, not just at the beginning of an adept's religious career, but all the way to the ultimate goal.

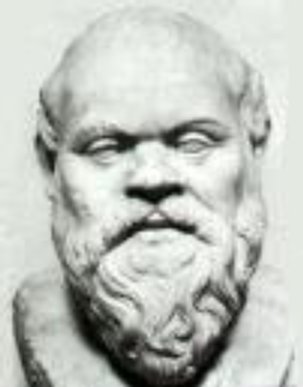

To anyone who has taken the time to read some of the works that have stood the test of time around the world, it is obvious that every culture has had people who answer to the description that Richard Tarnas offers of Socrates, as seen by Plato:

In Socrates, thought was confidently embraced as a vital force of life and an indispensable instrument of the spirit. Intellect was not just a profitable tool of Sophists and politicians, not just the remote preserve of physical speculation and obscure paradox. It was, rather, the divine faculty by which the human soul could discover both its own essence and the world's meaning. That faculty required only awakening. However arduous the path of awakening, such divine intellectual power lay potentially resident in humble and great alike.(Tarnas, 1991, p. 38)

Very similar claims could be made about any number of thinkers who never heard of Socrates, for as Mohanty has rightly observed:

If rationality is a universal, not limited by geographical regions, historical epochs, or cultural relativities, then philosophy as the purest form of rational inquiry must be, in its very conception, capable of being a universal pursuit of mankind. (Mohanty, 1992, p. 7-8)

In ancient India, one of the many people whose philosophical project was in important ways similar to that of Socrates was Gotama, the man who came to be known as the Buddha. Like Socrates, Gotama has inspired thinkers for the better part of two and a half millennia. To be sure, there are important differences between these two great thinkers, just as there are important differences between each of them and the many people who followed after them and took up aspects of their projects. I would agree with Karl Jaspers, who observed that no single category can be found to accommodate all that these men thought and enacted through their lives. I also agree with what Jaspers went on to say:

Their historicity and consequent uniqueness can be perceived only within the all-embracing historicity of humanity, which in each of them expresses itself in a wholly different way. To discover this common root has been possible only since mankind has achieved a unity of communication and the different cultures have learned of each other's crucial individuals. In an earlier day, each one was the only crucial individual for huge parts of mankind, and as a matter of fact has remained so even since the others became known. (Jaspers, 1962, p. 3)

What studying each of these great thinkers in the light of the others reveals is a common project of knowing the true nature of one's inner self by examining one's relation to the rest of the world. Not only is there an important similarity in the project, but there is also an important congruence of method, in that both these philosophers advised that self-knowledge comes most rapidly to those who discuss their ideas with others and allow themselves to be challenged by others who see the world in different ways and who can therefore see at least some of the flaws in one's own thinking. Rarely can people see the limitations in their own perspective as clearly as they can see the limitations in others' points of view. Therefore, dialogue is essential for one who wishes to achieve not just strength of conviction but genuine wisdom that has the power to raise one closer to what is both true and good. The task of the philosopher, it has often enough been said, is not so much to know answers as to raise questions. Philosophy, therefore, like science, is not a body of knowledge but a process of purposeful inquiry and critical examination. Both Socrates and Gotama were very good at this process, and yet each of them could probably have learned from the other. And we are living at a fortunate period of human history in which it is possible to benefit from both of them, as well as from the countless others who have followed in their footsteps.

In the short essays that follow, the process that is philosophy is illustrated, however poorly at times, by dialogs on a range of topics that have long been part of both the European and the Asian philosophical traditions. Among the issues raised are: What is the relationship between theology and philosophy, and between each of these and science? What are the limits of knowledge, and is there anything of which we can be certain? What is the distinction, if any, between historical narrative that can be taken as true at a literal level and mythic narrative that conveys truths about values through stories the literal truth of which does not matter? To what extent does our knowledge about the human body and the physical world constrain what we can reasonably and consistently believe about the possibility of the continuation of the consciousness that has been more or less continuous during our present lifetime? Is it reasonable for anyone to believe that there is only one articulation of truth that is valid for all people? Is there a single Truth or body of Truths that remains hidden to us but that nevertheless gives meaning to the many imperfect and limited truths that our ordinary minds can grasp? Grappling with just these sorts of question has always been the way of the philosopher. Grappling with these questions with a mind that has been strongly influenced by both the legacy of Socrates and the legacy of Gotama Buddha is currently the way of the Western individual who has gone for refuge to the Buddha. It is a way of using the mind that is not done just for the sake of flexing one's intellectual muscles but for the sake of being at least to some extent liberated from the limitations imposed by one's unexamined prejudices. It is done, in other words, for the sake of liberation, no less for the modern Westerner than it was for Socrates and Gotama. The writings that follow in the sections below offer at least a glimpse of how one Western Buddhist has, through dialog with others, gone about the important task of learning both his soul and the world.

Back to menu

Buddhism and materialism

June 6, 1995

There are two claims I have heard Buddhists making in recent discussions, both of which strike me as gross oversimplifications. One of those claims is to the effect that modern Western atheism implies materialism, and the second is that materialism is antithetical to Buddhism. Given that “materialism” is a word with many different meanings, I think it might be worth discussing which forms of materialism are and which are not antithetical to Buddhism.

As a point of departure, let me look at the nine senses of the term “materialism” given in Peter A. Angeles Dictionary of Philosophy. (Angeles gives eleven kinds, but two are quite irrelevant to our discussion here.)

1A. The mind (spirit, consciousness, soul) is nothing but matter in motion. Strictly speaking, there is no such thing as mind as an entity separate from matter.

No pre-modern Buddhists that I know of have embraced 1A. (I see no reason why one could not hold such a view. In other words, the view may be unprecedented among Buddhists, but that does not mean it is necessarily incompatible with the essential principles of Buddhism.)

1B. The mind does exist but is wholly dependent upon material causes; mind has no causal efficacy of its own.

Vasubandhu reports that some Indian Buddhists (some Vaibhāṣikas and some Sautrāntikas) held a view very much like 1B. Indeed, Vasubandhu himself seems to have endorsed a view somewhat like this. Later thinkers, such as Dharmakīrti, argued strongly against this form of materialism. So among classical Buddhists, this point was controversial, but even those who rejected it never said that it was incompatible with other Buddhist teachings.

2. Matter does not have such properties as purpose, awareness, intention, goals, meaning, direction, willing, striving, or intelligence. And, since the world is purely material, these things do not really exist at all.

This view, I gather, is something rather like what some modern psychologists believe; it has been reported to me by several students that virtually everyone in the psychology department at my university is a materialist in this sense. From what little I can remember from having the words of B.F. Skinner shoved down my throat as an undergraduate several æons ago, Behaviorism was somewhat similar to this view. I have never heard of any Buddhist endorsing this kind of materialism, and I think it might be at odds with some pretty fundamental Buddhist attitudes. Even so, I would be loath to say this kind of materialism is incompatible with Buddhism or antithetical to it.

3. There are no non-material entities such as spirits, ghosts, demons or angels.

The vast majority of pre-modern Buddhists were not materialists of this type, although quite early on there were Buddhists who suggested that such entities were projections of one's own imagination. Again, there is no reason at all why a Buddhist could not deny the reality of spirits and so forth without ceasing to be a Buddhist.

4. There is no supreme creator god.

The vast majority of Buddhist intellectuals and doxologists have been materialists of this kind. This is as true of Mahāyānists as of followers of the Nikāyas. Indeed, the most outspoken critics of the doctrine of a supreme god were followers of Mahāyāna; I refer to Dharmakīrti, Dharmottara, Śāntarakṣita, Kamalaśīla, Jñānaśrīmitra, Ratnakīrti and many others. In India, virtually every Hindu critic of Buddhism (especially the theists) categorized Buddhists as people who denied the existence of a supreme creator god. Clearly, this kind of materialism is not at all antithetical to Buddhism, but has historically been endorsed by all (with the possible exception of a handful of tantric) Buddhists and some Western Buddhists.

5. Every change has a material cause; everything can be explained in terms of material causality.

This is a more general version of 1A. It says of all things what 1A said of mental events. The same thing can be said about this as was said about 1A: it is unprecedented for Buddhists to hold this view, but there is no reason to think it is incompatible with essential Buddhist principles.

6. Matter is eternal in the sense that it was never caused by a prime mover.

The Buddha himself recommended against speculating about such issues, but the vast majority of Buddhist tradition did come to hold the view that the material universe is beginningless (another word for eternal) and had no creator. While any given material form is impermanent, the process of material causality is both beginningless and endless. Virtually all Buddhists have been and still are materialists in this sense. (At least I cannot think of any exceptions.)

7. Material forms may be altered, but matter itself can neither be created nor destroyed.

Buddhist atomists, such as the Vaibh¯asikas, held a view very much like this. While other Buddhists disagreed with them, no one (with the possible exception of David Kalupahana) has suggested that atomism is antithetical to the principles of Buddhism.

8. No life and no mind is immortal.

The vast majority of Buddhists would subscribe to this view and thus would be materialists in this sense.

9. Values do not exist in the universe independently of the activities of human beings.

This merely amounts to saying that values are created by people rather than discovered by them. I see nothing in this form of materialism that clashes with any principle of Buddhism. (Nor do I think that Western atheists are necessarily materialists in any sense except number 4.)

As I see it, not a single one of these nine senses of materialism is incompatible with Buddhism, even though some have not traditionally been held by Buddhists; and some of these kinds of materialism are actually endorsed by most Buddhists.

There is only one sense of the term “materialism” that strikes me as antithetical to Buddhism, and that is in the popular sense of the term: undue emphasis on material acquisitions as opposed to spiritual or intellectual improvement. It is in this sense, I take it, that much of Western (and most especially North American) culture is materialistic. And I would agree that this kind of materialism-the kind that minimizes the importance of intangible values such as civilization and virtue and moral integrity and maximizes the importance of striving for tangible possessions and physical pleasures and comforts-is profoundly incompatible with Buddhism.

In summary, I would say a Buddhist can very easily be a materialist (in the philosophical senses of the term) without compromising Buddhist principles in any way, but it would be much more compromising of Buddhist values to be materialistic. And of course there is no reason why a Western atheist, even one who was a materialist in every other sense of the philosophical term, would necessarily be materialistic.

Richard P. Hayes

Back to menu

Thinking philosophically vs. theologically

February 2, 1998

Charles Sanders Peirce, founder of the American pragmatist movement, wrote in 1898 that philosophy in general and metaphysics in particular had come to ruin in America because the teaching of philosophy was entrusted only to theologians. (Peirce's student John Dewey is said to be the first philosophy professor in the USA who was not an ordained Christian minister.) Theologians, said Peirce, are no more suited to do philosophy than are bankers and stock brokers on Wall Street. Ministers, bankers and brokers all suffer from the same defect: they are practical people who have definite tasks that they have set out to accomplish. Philosophy would best be left, said Peirce, to scientists, who have no concern with being practical.

The difference comes to this, that the practical man stakes everything he cares for upon the hazard of a die, and must believe with all the force of his manhood that the object for which he strives is good and that the theory of his plan is correct; while the scientific man is above all things desirous of learning the truth and, in order to do so, ardently desires to have his present provisional beliefs (and all his beliefs are merely provisional) swept away, and will work hard to accomplish that object (Buchler, 1955,pp. 311–312].

Peirce wrote before women lived on the planet, but one assumes his observations would be just as apt if translated in the gender-inclusive language required by 1990s etiquette.

The distinction that Peirce draws between the theologian and the scientist comes to mind as an antidote to the tedious scholar-bashing that manifests itself in Buddhist circles from time to time. The spirit of the Buddhologist is scientific in Peirce's sense of the word, for the Buddhologist is indeed one who “ardently desires to have his (or her) present provisional beliefs...swept away.” One thinks of a top-rate Buddhologist like Gregory Schopen, who has deeply imbibed virtually everything in print on the subject of Indian Buddhism—and hasn't believed a word of it. His is a scientific spirit par excellence, and I daresay that many of us on this list have been possessed by the same spirit.

The worry that seems to hound the minds of the theologians and bankers and brokers in the Buddhist community—those who distinguish themselves as admirers of real practitioners as opposed to mere scholars—is whether being a scientific scholar is in any way compatible with being a person of the Dharma. Let me try yet again to lay that worry to rest.

Śāntarakṣita wrote a verse to the effect that the Buddha roared a lion's roar that silenced all the lesser philosophers (kutarka), whose disputes were like the cacophony of elephants during the mating season, for the Buddha alone dared to say “Do not believe what I have said until you have tested it as a goldsmith tests whether a metal is true gold or fool's gold.” The commentator Kamalaśīla adds that this is an invitation to test all the doctrines of Buddhism in the crucibles of experience and reason and to throw out the contradictions as the jeweler throws out the dross.

Śāntarakṣita and Kamalaśīla were continuing a very old trend in Buddhism, one that extends at least as far back as Dignāga. This school of thinkers swept aside all the sectarian disputes over which sūtras were authentic records of the Buddha's sayings and which were later forgeries. The question of what the Buddha actually said became a much less important question than the question of what is actually true.

Once one begins to look for truth instead of Buddha-vacana (sayings of the Buddha) in the sūtras, not much survives. About all that one has left at the end of the day is the Four Noble Truths—not much, but perhaps just enough.

Now I contend that the four noble truths taken together form an hypothesis that one can ponder with a scientific spirit, in the Peircean sense. For never was there a view of the world that one would wish more fervently could be swept away and dismissed as falsehood or the ranting of a lunatic. If the Christian teachings are evangel (good news), the Buddha's first sermon was surely dysangel (bad news).

“Everything is disappointing to one who has unrealistic desires. Disappointment stops only when desire ceases. And then you die, never again to appear anywhere in any form.” (The short answer to a Benedictine friend who asked “Isn't there more to Buddhism than this?” is “No, damn it.”)

As I have already said, many modern Buddhologists (not all to be sure) examine what they study with a scientific spirit, with not only a willingness but a will to disbelieve. And I would contend, against the theologians among us, that these Buddhologists are also practicing a very old and much venerated form of Buddhist meditation, known since the time of the Pali canon as critical thinking (yoniśo manaskāra).

If you are a theologian, critical thinking may not be the raft you have personally chosen to get across the flood. But it is a raft all the same. So if you find yourself feeling an urge to reproach the scholars for what we have chosen to navigate the rapids, please remember that there is much more to be gained by minding your own raft and letting us mind ours.

Perhaps when we all meet on the other shore we can have a picnic. But there will probably be ants.

Richard P. Hayes

Back to menu

American views of Buddhism

June 8, 1993

When all else fails, it is occasionally helpful to try to place controversial issues into an historical perspective. It's not that historical investigations can solve truly philosophical problems, because truly philosophical problems are precisely those that can't be solved by any methods. But what historical understanding can sometimes do is provide an occasion for self-reflection; knowing the history of a debate can often help one understand one's own attitudes a little more clearly.

As those of you who are familiar with the history of American philosophy will readily recognize, many of the messages I have posted here represent one side of a dispute that has been going on for well over a hundred years. At the risk of oversimplification, American philosophy in the nineteenth century was divided into two camps. On the one hand there were those who were strongly influenced by the various monistic and absolutist trends of German idealism, and on the other there were those who were influenced by empirical science and scientific skepticism.

The Monists and Absolutists tended to be convinced that there is a unity underlying all the apparent diversity and conflict in the world. They often sought to reconcile religions by arguing that all religions are fundamentally one at the core. There was a great deal of exciting cross-fertilization of ideas among intellectuals all over the world, and one can find Hindu thinkers of this period (see Vivekananda, Dasgupta et al) passionately seeking the influence of classical Indian philosophy on the likes of Kant and Hegel who could then be used as avenues of approach into the profound mysteries of classical Indian thought. On another front, one finds the Japanese scholar D.T. Suzuki presenting Zen as a kind of Absolutism and claiming that True Zen (as opposed to sectarian zen) is the Unity underlying all diversity. In Persia, the Bahá'í movement can be seen as a manifestation of this drive to find the harmonizing principles in all apparent conflicts, and it spread rapidly into the world arena. And New York gave birth to the Theosophical movement.

The scientific and empiricist opposition to monist thinking was also an international phenomenon, but it was particularly robust in the United States. The thinkers who called themselves Pragmatists (Charles Sanders Peirce, William James and John Dewey) were as adamant in their celebration of radical pluralism as their philosophical rivals were in their celebration of ultimate non-dualism.

Dewey, following James, wrote that Monism necessarily goes hand in glove with authoritarianism, determinism, dogmatism and rigidity in thinking—all the characteristics the Pragmatists most dreaded. He went on to say:

Pluralism, on the other hand, leaves room for contingency, liberty, novelty, and gives complete liberty of action to the empirical method, which can be indefinitely extended. It accepts unity where it finds it, but it does not attempt to force the vast diversity of events and things into a single rational mold. (Dewey, 1973, p. 46)

What is interesting for our purposes here is that both the Monists and the pluralistic Pragmatists discovered Buddhism, and both found in Buddhism an adumbration of their own philosophical positions. Of course both sides also found plenty in Buddhism that didn't suit their tastes, but they all felt free to discard what didn't appeal to them. The scientifically oriented Pragmatists divested Buddhism of its ritualism and supernatural elements, while the more mystically inclined Monists gently set aside much of the scholastic tradition of Buddhism as so much monkish prattle.

Also interesting is that this debate among American and European intellectuals had profound consequences on both Hinduism and Buddhism. Read the chapter entitled “Protestant Buddhism” in Richard Gombrich's Theravāda Buddhism: a social history from ancient Benares to modern Colombo for some of the sweeping changes in Buddhism in Sri Lanka as a result of the influence of Protestant missionaries, British jurisprudence and various European-trained educators. Read the section in that chapter on the tremendous influence of the Theosophical Society in the reform of Theravāda Buddhism.

My point here is not to take sides in this dispute (since I do plenty of side-taking in my other writings), but rather to draw attention to the fact that the conflict is still very much alive and to suggest that most of us are, whether fully aware of it or not, still participating on one side or the other of this long-standing philosophical debate between Absolutists and Pragmatists.

For North American Buddhists and scholars of Buddhism interested in how Buddhism was first received in America, there is a relatively new book by Thomas A. Tweed, The American Encounter with Buddhism, 1844-1912: Victorian Culture and the Limits of Dissent. There is a good amount of discussion there of the influence of the Theosophical Society on American perceptions of Buddhism, and also of the influences of various other American intellectual movements.

Thomas A. Tweed also has a fascinating article in the Journal of the American Academy of Religion called “An American Pioneer in the Study of Religion: Hannah Adams (1755-1831) and her Dictionary of All Religions.” It's an informative article and has some very amusing comments on how a contemporary of Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin regarded Buddhism. (It is also an interesting corrective to the perception that may linger that the efforts of women scholars were not appreciated in colonial America.)

Richard P. Hayes

Back to menu

Socrates, Siddhārtha and Sunim

May 28, 1994

Marc reports:

Supposedly Socrates used to tell his students: “You must know yourself.” Once a student asked him whether he would know himself. Socrates replied “I don't know, but I understand this not-knowing.” (Told by Seung Sahn in his book Dropping Ashes On The Buddha.)

Zen masters really ought to confine their activities to misquoting the Buddha. They go too far when they misquote Socrates! (If he had said this at my university, Sunim would almost surely have been sued for uttering racist slurs against Greeks.)

About a particular man who thought he knew something but was unable to give an adequate account when questioned by Socrates, Socrates said “It seems that I am wiser than he is to this small extent, that I do not think I know what I do not know.” (Apology 21e)

Further on in the Apology (29b), Socrates claims that he knows nothing about what happens to a person after death, and he says “Perhaps I differ from other men in this way, and if I were to say that I am wiser in anything, it would be in this: that not knowing very much about the afterlife, I do not think I know.”

Socrates did not, however, claim to know nothing at all. He did claim to know this: “It is evil and disgraceful to do wrong and to disobey him who is better than I, whether he be god or man.” And he also claimed to know that he had been sent by God (31a) to show the citizens of Athens that human wisdom is of very little value when compared against divine wisdom. “I am wise in the matters in which I refute others,” he said, “but the fact is that God is truly wise and probably means to say through his oracle that human wisdom is of little or no value.” (23a) Recall also the final words in the Apology: “But now the time has come to go away. I go to die, and you to live; but which of us goes to the better lot is known to none but God.” Socrates claimed to know that life is not worth living unless every day is spent in examining oneself and knowing how one is doing in the pursuit of virtue (38a). This is in fact what Socrates meant by the dictum “know yourself”; he meant know to what extent you are being virtuous according to divine, not human, standards of virtue.

Socrates called upon his own state of poverty as a witness to the fact that he spoke the truth (31c), and he declared that anyone who speaks the truth in a public forum is sure to make most people angry (31e), and anyone who fights for justice in a public forum is unlikely to preserve his life for very long (32a). (As someone pointed out recently on an e-mail forum for the discussion of philosophy, Socrates would surely have been much too wise to use any forum as public as a modern university or the Internet.)

On the one hand, there are some similarities between the Buddha's attitudes and those of Socrates. They agreed in their disdain of those who pretend to know what they do not really know. The Buddha is reported to have said: “It is appropriate indeed to be uncertain when that about which one ought to be uncertain is present. But when you yourselves know that some teachings are unhealthy and shameful and reproached by the wise and that acting on them leads to harm and pain, then you must reject those teachings.” This is an abridged version of the celebrated advice to the Kālāmas in the Aṅguttara-nikāya.

Like Socrates, the Buddha presented himself as knowing some things, especially some things about virtue and good character, with certainty. On the other hand, the Buddha would surely have laughed at Socrates, just as he laughed at all men who claimed to know the mind of God or pretended to understand the divine standard against which mere human wisdom is inadequate.

Socrates would most probably have mistrusted the Buddha on the grounds that he claimed to be a teacher and a guide of both gods and men. Socrates insisted he was not a teacher: “I ask questions, and whoever wishes may answer and hear what I say. And whether any of them turns out well or ill, I cannot justly be held accountable, since I never promised or gave any instruction to any of them.” (33b).

Although I cannot be sure, I suspect that many Euro-American Buddhists find themselves trying to find some balance between the Socratic and the Gotamic ideals of wisdom, in much the same way that most Asian Buddhists find themselves trying to find some balance between the Confucian and the Gotamic notion of the Way.

Sometimes people who try to do impossible balancing acts fall into some interesting positions.

Richard P. Hayes

Back to menu

What unity?

June 13, 1995

It has been said that every issue in metaphysics is some version of the riddle of how unity is related to diversity. There have always been thinkers who stressed the primacy of the whole, of the underlying unity of all things. In its most extreme forms, this view may take the form of some expression to the effect that the unity is alone real and all diversity is to some extent illusory. This view, called advaita (non-dualism) in Sanskrit, has its representatives in Hinduism and in Buddhism. Countering those holists who stress unity, there have always been those who placed a greater stress on diversity, even to the extent of claiming that unity is merely an illusion or a figment of the mind struggling to make some sense of the bewildering diversity.

Among the most radical pluralists in the history of philosophy one finds numerous Buddhists, especially in India and Tibet. The Theravāda, Sarvāstivāda and Sautrāntika schools of abhidharma were all, to varying degrees, radically pluralistic. They tended to be nominalists, that is, people who say that wholes, such as persons and other things, have no existence aside from the existence of their components and that names of wholes are merely shorthand ways of referring to a collection of parts. This was clearly the position of Nāgasena in the Questions of Milinda and of Vasubandhu in the Abhidharmakoṣa; one reading of Nāgārjuna is that he was also a staunch nominalist. Most of the later Indian epistemologists were also nominalists.

Nominalism is a philosophical stance that stands opposed to holism, rejects the notion that there is a universe operating as a unified and coherent system, and tends to dismiss the idea of a cosmos (an order that stands in contrast to chaos). Much of Buddhist abhidharma, I would argue, is anti-holistic and acosmic in nature. And this feature, I think, accounts for much of the resistance that one finds among Westerners to abhidharmic modes of thinking.

Western civilization tends to be overwhelmingly holistic and cosmic in predisposition. Ever since the Greeks, there has been a tendency to find the one substance out of which all plurality emerges, the one cause to which all things can ultimately be traced. Ever since the Enlightenment, Western scientists have sought to find the one theory that explains everything, the Big Bang, the Unified Field Theory, the Theory of Everything. No matter how uncooperative reality persists in being, Western scientists are loath to give up the notion of some kind of underlying unity or fundamental interconnectedness of all things. There is a real reluctance to abandon the idea that somehow all this vastness of time and space is a universe, a single system operating under a consistent and coherent set of universal and invariable laws. One might call this view the main prejudice of post-Enlightenment thought. It affects every discipline, including religious studies (where one can still find people who seek an underlying unity to all the world's religions, despite a great deal of apparent evidence to the contrary).

Having been brought up in a scientific family during two decades in which it was widely believed in my native country (by everyone except the more advanced scientists) that science was far more important and far more in touch with the fundamental realities than the humanities, there was never any question in my mind about what I would eventually devote my life to. I was clearly headed for a career in mathematics and science.

For reasons that I will probably never completely understand (could it have been the experiments with peyote?), in the first semester of my second year of college, I had a crisis of faith. I can still vividly remember sitting in a biology class and copying down page after page of notes on the formulas of complex molecules, and suddenly I just set my pen down and thought “These guys are just making all this stuff up. This whole enterprise is just a matter of stacking one fanciful model upon another, and explaining one speculative theory by another even more speculative. And they're doing all this because they can't let go of the idea that there must be one explanation that accounts for everything.” I was overwhelmed with the lack of coherence and unity in the world. The whole universe instantly dissolved into billions of unrelated and inexplicable fragments; for just a moment, I was utterly confident that all apparent order was a total illusion and that absolutely nothing could be explained, that none of this made any sense whatsoever, and the very idea of trying to make sense of any of it is the laughable undertaking of imbeciles who are incapable of seeing the underlying chaos for what is really is. (Some people get enlightened; wouldn't it be my luck to get endarkened!)

After that revelation of sheer chaos underlying all apparent cosmos (which, for all I know, may have been a cerebral stroke or an epileptic fit), I stopped going to classes, failed all but one of my courses, quit school and took a job cleaning toilets at a YMCA camp in California. Cleaning toilets was the only way I could think of to purge myself of the intellectual conditioning I had received as a child. There is something therapeutic about a dirty toilet; it puts one back in touch with the important fact that we human beings are always trying in vain to flush unpleasant realities out of reach of the senses, to get rid of them so that we never again have to think of them. A dirty toilet helps one to see very clearly that such concepts as God, Brahman, the Ādi-buddha, the Tathāgata-garbha, the Dharma-dhātu, the Plenum, the Absolute, the Big Bang and the Theory of Everything are merely philosophical toilets down which we try to flush the unpleasant reality of metaphysical chaos and the inexplicability of things and the fundamental meaninglessness of life. (I say this not in despair but with a cheerful heart that has thrown of the burden of feigned understanding and false meaning.)

Somehow—it would be inconsistent with my beliefs to try to explain exactly how—, I have found that Buddhism is the only religion that enables me to deal effectively with a world that is beyond understanding and with a life that just sort of happened and continues to happen without rhyme or reason and then just comes to a largely unnoticed end. Buddhism does not foist explanations off on me. It is important to me to keep at least some forms of Buddhism alive that will remain serviceable to people who have had experiences like those I have had. Other people, of course, have other kinds of experience; I am more than happy to let them keep those forms of Buddhism alive that will remain of use to them, so long as they do not try to obliterate the forms that are of use to me. It is worth bearing in mind, I think, that there are basically two kinds of people in the world: those who believe there are basically two kinds of people in the world, and those who don't.

In keeping with the way I see things, this essay is utterly pointless. I had no reason for writing it. Having written it, I now dedicate it to all sentient being in the hopes that at least some of them will learn to feel at home in an inexplicable universe.

Richard P. Hayes

Back to menu

Pluralism

March 21, 2002

A reader named Nanda opines:

There can be multiple “ways”—but only based on one understanding, which all the “ways” have to finally reconcile with.

That is just one understanding. Yours. My understanding is rather different. I would say that there are many truths, many understandings, many goals and many ways of reaching them. And they are all valid, all capable of bringing deep and lasting satisfaction. Nothing you have said convinces me otherwise. This is my deeply entrenched prejudice. Your deeply entrenched prejudice is different from mine. Neither of us can persuade the other. But that is fine, because there is really no need for everyone to agree and see things the same way and have the same understanding. Why? Because there are many equally good understandings and many ways to reach a plurality of goals, any one of which can be ultimately satisfactory to the people who achieve them. In other words, I am right. But then again, so are you, in your own way.

My beloved companion in life and love has a T-shirt that says “There is One Truth and there are Many Paths.” I let her wear it, even though I believe “There are Many Truths and to most of them there are Many Paths.” I can easily imagine that someone else might have a T-shirt that says “There are Many Truths, but there is only One Path.” And God knows there are enough people out there who say “There is but One Truth, and there is but One Path.” The world is varied, n'est-ce pas? And each of us has to find a way of not letting that variety get us down. Some study, think, laugh and cry. Others look at finger bones in reliquaries. And some of us do a bit of everything and get quite a kick out of everything we do and derive a great deal of joy watching others get a kick out of doing what they do.

Richard P. Hayes

More on pluralism

22 March 2002

About what I said on pluralism our friend Nanda asks:

You said “There are Many Truths and to most of them there are Many Paths.” Whatever your personal preferences might be, still do you think such a stance is compatible with Buddhism?

I have never understood Buddhism as a creed with which one must agree. I have understood Buddhism as a strategy of identifying what causes misery and then trying to remove those causes in order to remove misery. When I look at the world around me, I see that quite a lot of misery is caused by people being quite sure that what is good for them is also good for everyone else. This conviction all too often leads to some people imposing their solutions to the problems they perceive onto other people. (Why else would some people hijack airplanes and fly them into tall buildings? Why else would a president feel it necessary to threaten to drop nuclear bombs on “evil” countries that do not accept his particular version of what freedom and democracy consist in?)

In the world in which we now live, a great deal of avoidable pain, misery, suffering, destruction and death is fueled by people who believe there is but One Truth. One way to counter that kind of disease is to discuss alternatives to the One Truth model. One such alternative is pluralism. Promoting pluralism in order to help reduce needless suffering is my strategy. Employing any strategy at all to reduce needless suffering is, it seems to me, the very essence of Buddhism.

... for the Buddha clearly didn't think so as he claimed that all paths in his time fell into the extremes of either eternalism or nihilism and it was only his path that was the true one which was “excellent in the beginning, middle and end.”

That was more than 2500 years ago. The Buddha probably never saw any of the world farther from his home than about 300 km. A great deal has changed since his day, and not to try to take some of those changes into consideration is a blindness of potentially catastrophic implications. Nothing at all is permanent, including the applicability of any one formulation of the Dharma. So please do not be so rigid that you use a literal reading of the Pali or any other canon as the sole criterion by which you assess your or anyone else's authenticity as a Buddhist.

Now as for your specific claims, when the Buddha was asked (according to a sutta in the Aṅguttara-nikāya) whether various other ascetic (samana) teachers were leading their disciples to nibbāna, his reply was “I don't know. I have not had an opportunity to observe their disciples long enough to know whether or not they have become liberated.” He could have said, “Hell no, they can't possibly lead anyone to nibb¯ana, because only I have taught the One Truth that shall make men free.” That he did not avail himself of the opportunity to say on this occasion that he was the only person teaching an efficacious doctrine suggests to me that he thought it at least possible that other teachers were also teaching effective doctrines.

On another occasion (Brahmajala Sutta, Dīgha-nikāya), when the Buddha overheard his own disciples claiming that their teacher was the greatest and that no other teacher was leading their disciples to nibbāna, he chastised his disciples and said they were betraying him by saying such irresponsible things and by misreporting his teachings. On yet another occasion (Mahāparinibbāna Sutta, Dīgha-nikāya), when Sāriputta claimed that Gotama was the greatest teacher who had ever lived, the Buddha chastised him by asking “How do you know, Sāriputta? Have you studied with every teacher who ever lived?” He then urged Sāriputta to be content with saying that Gotama had taught a version of Dharma that enabled some people to become arhants. This does not imply at all that no one else teaches a version of Dharma that enables other people to become arhants.

If we look very carefully at the people whose teachings the Buddha did single out for criticism, we find that his reason for doing so was that these people were advocating irresponsible behaviour. They were advocating hedonism and denying that actions have consequences. People who were not advocating moral irresponsibility were not criticized. What this suggests to me was that the Buddha adopted neither the stance of saying “Only I teach the True Dharma” nor the stance of saying “Everyone's teaching is just fine.” What he seems to have advocated is a careful scrutiny of teachings with an eye to seeing what in them was useful and what in them was counterproductive.

And can Nāgārjuna's “The Tathāgatha at no point in time taught any dharma at all” be interpreted as a “no path at all” approach?

What I think Nāgārjuna was getting at is pretty much exactly the same thing that the Buddha was getting at when he said “The sage takes no sides in a dispute” (Sutta-nipāta). Taking sides leads to all manner of hatred, dissension, disharmony, conflict and warfare.

As Steve Collins has argued with admirable clarity in chapter 4 of Selfless Persons, what the Buddha seems to have been most interested in was not coming up with a catalog of which views are Right and which are Wrong. Rather, he seems to have been most interested in pointing out that when anyone is attached to any view whatsoever, whether it is right or wrong by any criterion of truth that one may wish to press into service, the result is dukkha. Attachment to views, just like attachment to anything else, can lead only to disappointment. And disappointment, as Śāntideva pointed out, is the fuel of hatred and contempt. So attachment to views can be a terribly pernicious disease. The Buddha knew that. So did Nāgārjuna. That is why Nāgārjuna said “The Buddhas taught emptiness as an antidote to all views. But anyone who makes emptiness into a view the Buddhas declare incurable.”

To answer your question as to whether I think pluralism is compatible with the teachings of the Buddha, I would say Yes. I don't see any problem at all. Do you? If so, then don't preach pluralism. I won't mind at all.

Richard P. Hayes

Back to menu

References

- [Buchler 1955]

- Buchler, Justus, editor. Philosophical Writings of Peirce. New York: Dover Publications, 1955.

- [Dewey 1973]

- Dewey, John. “The Development of American Pragmatism.” The Philosophy of John Dewey. Ed. John J. McDermott. University of Chicago Press, 1973.

- [Jaspers 1962]

- Jaspers, Karl. Socrates, Buddha, Confucius, Jesus: The Paradigmatic Individuals. Ed. Hannah Arendt. Translated by Ralph Manheim. Originally part of volume one of The Great Philosophers, a translation of Die großen Philosophen. San Diego, New York, London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, 1962.

- [Mohanty 1992]

- Mohanty, Jitendranath. Reason and Tradition in Indian Thought: An Essay on the Nature of Indian Philosophical Thinking. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- [Tarnas 1991]

- Tarnas, Richard. The Passion of the Western Mind: Understanding the Ideas That Have Shaped Our World View. New York: Ballantine Books, 1991.

Back to menu

File translated

from TEX by TTH, version 3.00.

File translated

from TEX by TTH, version 3.00.